LAREDO — The high walls of Alexander Estates, an affluent development nestled near this border city’s country club and golf course, were supposed to keep the narcotics world at bay. But when federal agents raided the stately home of a downtown perfume salesman in January, it reinforced a notion that is feared by Texas leaders: The drug war spillover from Mexico is much broader than shootouts and kidnappings — it is cloaked in the seemingly routine business transactions of the border economy.

Neighbors stood, mouths agape, as federal agents seized loads of cash from the home of Vikram Datta, a polite family man who acquaintances said was so concerned with the quality of Laredo schools that he moved his teenage daughters back to their native New York. Federal agents leveled an accusation that shocked other residents: that Datta, 51, was a major player in the Black Market Peso Exchange, a decades-old system of laundering drug money and reinvesting it back into the economy.

According to Datta’s lawyers, who declined to make him or his family available for interviews, their client is a legitimate businessman who was entrapped by other drug-connected defendants to get lesser sentences for their own money-laundering schemes. But prosecutors contended, and a federal jury agreed in September when it convicted him on two counts of money-laundering conspiracy and one count of conspiracy to violate the travel act, that Datta’s sales of millions of dollars worth of perfume to corrupt buyers in Mexico were fueled by greed. He knew, they said, that the underground drug economy — involving some of the world’s largest suppliers of narcotics to North America — would make him rich.

Getting inside

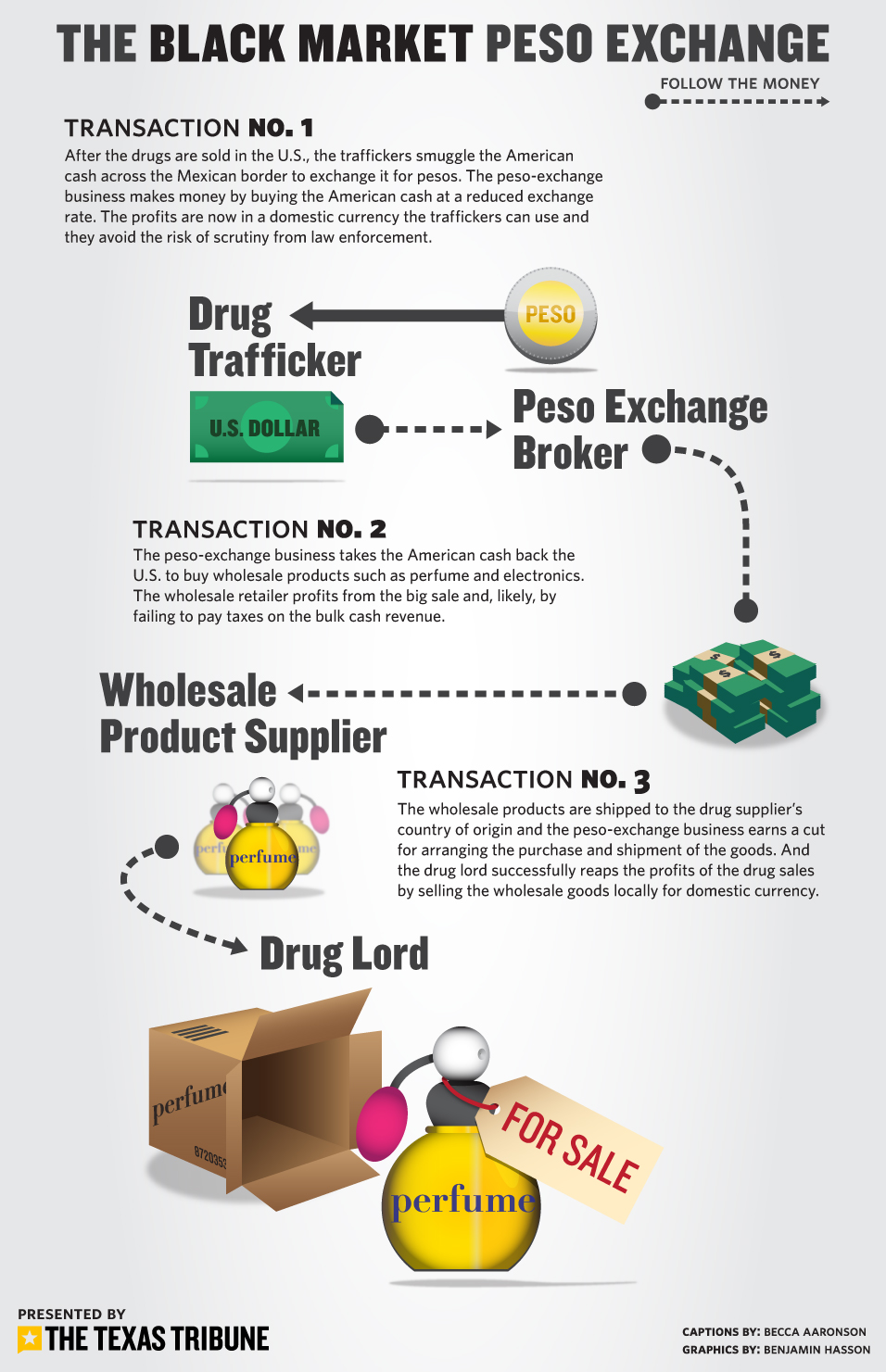

The Black Market Peso Exchange has been on the federal government’s radar for years. The system was perfected by Colombian drug lords and later adopted by Mexican drug cartels: When drugs are sold in the United States, the proceeds, in American dollars, are smuggled back into Mexico or Colombia, where they are exchanged for pesos at a discounted rate.

The peso-exchange businesses then use the dollars to buy products in the United States — in Datta’s case, millions of dollars worth of perfume — and have them shipped to purchasers in Mexico or Colombia.

The Department of Justice created a task force to infiltrate the American businesses cooperating with these money-laundering schemes, initially targeting Colombian drug dealers buying computer parts in New York according to prosecutors. On wiretaps, investigators learned of a similar market in Mexico, this time involving American perfume wholesalers.

In Laredo, Datta, an immigrant from India, was basking in financial success. He had come to the United States in 1983 and became a naturalized citizen in 1994. On a business trip to Laredo in 2000, he discovered that inland port’s gold mine: a downtown merchants sector where millions of dollars in goods and cash exchange hands every week.

Just a year after renting his first retail space in Laredo, Datta had four profitable perfume stores in the city in addition to operations in New York, Arizona and California. He was making $30 million in annual sales, his lawyer said.

Federal prosecutors, however, said that by 2009 Datta was an experienced money launderer for Mexico’s Sinaloa drug cartel.

“All Sinaloa money”

In 2009, the Justice Department task force focused an investigation on Ajay and Ankur Gupta, father-and-son perfume vendors in New Jersey, were accused of playing in the black market and, over a decade, netting millions of dollars. Datta’s lawyers said they were known for careless transactions like picking up plastic-wrapped bulk cash in parking lots behind fast-food restaurants. When they were arrested, Datta’s name surfaced in their records, and Datta’s lawyers said the Guptas agreed to help implicate some of their business partners in order to shorten potential 20-year sentences. The Guptas’ lawyers refused to comment because their clients still face money-laundering charges.

An attorney for Datta said the Guptas tried repeatedly to draw in Datta, trying to give him large cash payments, which he refused. Finally, prosecutors said, he accepted. At a 2010 trade show in Las Vegas, the Guptas introduced Datta to someone they claimed was a perfume vendor from Baja California Sur, Mexico. The man was actually an undercover federal agent.

Datta’s illegal transactions started slowly but quickly increased, court documents indicate. Transcripts from wiretaps over the next six months, which were admitted at trial, indicate that Datta accepted a $40,000 infusion to one of his stores in California and later agreed to wire $100,000 to customers in New York. According to court documents, over the course of a two-year government sting, he and other co-conspirators deposited more than $25 million of American currency in dozens of bank accounts.

At one point, prosecutors said, Datta told an undercover agent, posing as a perfume vendor, that his business was “just washing the whole money.” In a conversation that he had with the agent in New York in December 2010, captured on wiretap, Datta said that “a lot of cash is coming to me” and that he was “90 percent sure” that it was “all Sinaloa money.”

In the same conversation, the agent told Datta he had not been completely honest with him. “I’m moving kilos for the Sinaloa,” the agent said. Datta replied, “Okay.”

Alan Ross, Datta’s lawyer said: “He smelled that this guy was an illegal man, that he was repping himself to be a money launderer. Normal instincts would be to run, but greed got the best of him.”

A crucial kidnapping

If Datta was not already convinced that his perfume vendor partner was part of the cartel, the kidnapping of a former client in Mexico City sealed the deal. Datta called the undercover agent — who, unknown to him, had been listening in on his phone calls about the kidnapping — to ask if he held any sway in getting the man released.

The agent hedged, pretending to know details of the kidnapping. Purely coincidentally, the kidnapped man was set free. Datta, elated, booked a flight to New York, Ross said, to thank his “friend” — the undercover agent — and “kiss the godfather’s ring, so to speak.”

But when Datta got to Manhattan in January, the authorities arrested him and charged him with conspiracy to commit money laundering. He was convicted after a two-week jury trial, and now awaits sentencing, facing a $1 million fine and up to 45 years in prison. To date, 29 people have been charged in connection with the Black Market Peso Exchange; 20 have been convicted Lawyers for Datta plan to appeal his conviction. Last week, they filed a motion for a retrial or an acquittal, claiming insufficient evidence to sustain a conviction. They said his story was a cautionary tale, one of an ambitious businessman whom federal agents lured into the nefarious underworld of money laundering.

The government prosecutes people and, in this case, convicted him probably because he didn’t go out and take affirmative steps to find out where customers in Mexico, where they were buying their U.S. dollars,” Ross said. “No one told him that. He didn’t know.”

But prosecutors said that a cursory glance at the bread-crumb paths that made Datta his fortune would have easily led him to drug money. During his trial, Datta testified that his actions were driven by “greed.”

Datta “tried to mask dirty money with, of all things, the scent of perfume,” Preet Bharara, the United States attorney for the Southern District of New York, said in a statement after Datta’s arrest. “But as this case demonstrates, even the sweetest-smelling money-laundering scheme is no match for determined law enforcement.”

“We didn’t care”

On a recent day in Laredo, just blocks from the pedestrian bridge that connects Texas to the Mexican state of Tamaulipas, Les Norton, the executive director of the Downtown Merchants Association, spoke fondly of Datta.

As Norton, the owner of La Fama clothing store, stood across from the perfume store the Datta family still runs in the heart of downtown, he said that when his own mother died last year, Datta was the only member of Laredo’s small but prominent Indian community who called to offer his condolences.

Despite Norton’s disbelief that Datta could be tangled up in a criminal scheme, Norton said the millions of dollars his friend was convicted of exchanging for perfume was hard to fathom. Even in Laredo’s heyday, Norton said, before Tamaulipas fell into the stranglehold of drug cartels and wait times tripled at border crossings, his own biggest bulk sales of blue jeans came nowhere near Datta’s figures.

“The stories, the rumors that you hear are mind-boggling,” Norton said. “That blows my mind, that one customer wanted to buy millions.”

Still, he acknowledged that in the border marketplace, money could be difficult to track.

“If you go back years ago, be- fore the economic downturn, yeah, we would have big sales,” Norton said. “We didn’t care who it was. As long as we didn’t have counterfeit bills and the credit card went through, that’s what we were interested in.”